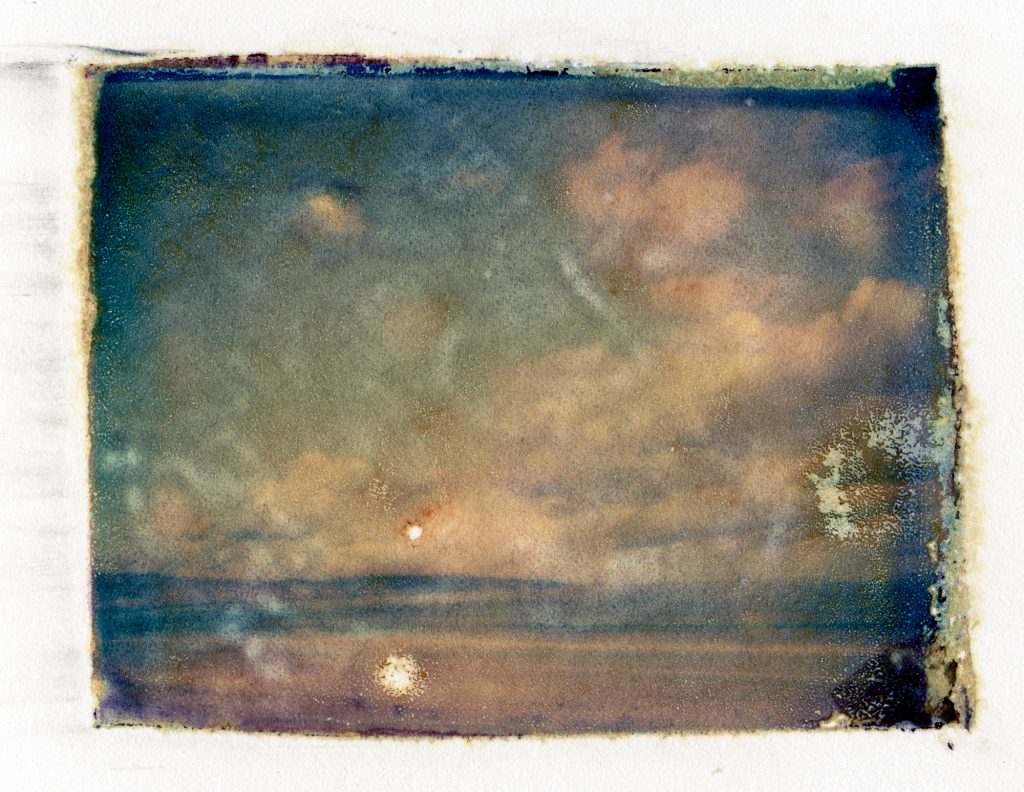

This series of low-light seascapes is evolving from the Fleurieu works 2019-2023. It is an examination of the pure beauty of water, air and light captured simply in photographs. The work aims to move the human element away from centre-stage and to honour the natural world and the intricacies of its structure and the physical laws that govern it.

Works in Progress:

This page will develop as new works are created and become part of the series.

Review:

Here is a preliminary review of work in progress: This work will be exhibited in March 2025: https://www.newmarchgallery.com.au/events/collective-visions-a-showcase-of-contemporary-adelaide-photography

The Luminous Threshold: David Hume’s Search for the Sublime

In the shifting, ephemeral world of David Hume’s seascapes, water is never just water. The ocean is a boundary, a threshold, a reflective surface for the unseen. His images—long exposures of roiling seas under dusk-heavy skies—do not merely depict the ocean; they evoke something closer to memory, or reverence. If photography is often accused of fixing moments too neatly in time, Hume’s work resists this tendency. Instead, his images seem to breathe in slow, rhythmic cycles, as though time itself were subject to the moon’s pull.

Hume, an Australian visual artist and fine art photographer, has spent years refining his distinctive vision of the sea, balancing its mathematical precision—the physics of light, the play of exposure—with the ineffable, a sense of the sublime that recalls J.M.W. Turner’s roiling tempests. In his latest work, the ocean is less a subject than a medium for light itself. His compositions, often minimal, eliminate the horizon or let it dissolve, merging sky and water into a single, spectral field of blue and silver.

Physics and the Sublime

Photography, at its core, is an act of physics: light, lens, exposure, capture. But Hume’s fascination with light goes beyond mechanics; his seascapes find their depth not just in the image itself but in what lies beneath—the scientific elegance of optics, the immutable laws that dictate how water moves, how light bends.

His recent works, large-format pigment prints on fine art paper mounted to Dibond aluminium panels, have an almost painterly stillness. The surfaces, though smooth, invite tactile engagement; one wants to press a hand against them, to feel the weight of time they seem to hold. Unlike Turner’s violent, kinetic storms, Hume’s oceans are quieter, more meditative. They recall, in their measured compositions, Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Seascapes—but where Sugimoto’s oceans are distant, elemental, Hume’s have a warmth, a luminosity that is unmistakably Australian.

The question that underpins much of his work is an old one, stretching back to the Romantics: can the sublime be captured, or does the attempt to fix it in place negate its very nature? Hume’s answer, implicit in his images, is that the sublime is not found in grand gestures but in the quiet interplay of light and space, in the way the sea dissolves into air.

A Measured Reception

In the contemporary art world, where conceptual gestures often outpace aesthetic concerns, Hume’s work occupies an unusual space. He is a photographer, but his process and intent align more closely with painters. His approach is methodical, his images deeply considered. Critics have responded accordingly: some, particularly in Australia, have praised his precision, his ability to translate motion into stillness. Others have questioned whether his restraint veers too close to the decorative, mistaking its refinement for detachment.

But Hume’s work is not detached—it is deeply, if quietly, engaged. His images suggest that beauty, in its purest form, is not a retreat from complexity but an acknowledgement of it. They ask us to stop, to see not just the ocean but the act of seeing itself. And in a time of perpetual acceleration, of images designed to be scrolled past rather than looked at, this is no small thing.

Recently Exhibited:

Where it Began:

I’ve been making images in this area for 30 years or so.

Recent History:

I returned to photography as a fine art medium in 2020 after a break of many years. At this time I started to incorporate other mediums (mainly hand-colouring and overpainting in oils) into the works. If the above work is of interest you may wish to check out the following.

2023: Fleurieu – Perceptions of Place. Inaugural SALA Photographic Opportunity Recipient of 2022 See more