Conversations with Cezanne – August 2018

Listen to an interview Rod and I did on Radio Adelaide:

One Sunday morning, about six months ago, the early sunlight hit a bowl of lemons in my kitchen, and all of a sudden there was Cezanne. He had turned up in my house and he decided to stay a while.

To be fair, I guess he had been popping up more and more over the past couple of years. I saw him once in a cathedral in France with his colours shining through the stained glass, and I also remember him as I was riding my bike through a railway tunnel one morning. “Why do we seek to divide nature?” he asked that day.

I didn’t really get him when I was very young, but at age twenty seven I saw a still life of his in the Met in New York and the power of it threw me out of the room. Just the red of the apples and the blue of the cloth, but it was so powerful that I did not have the strength to stand in front of it.

So that’s thirty years ago, and in the mean time my own work had become so abstract that it had almost disappeared. It needed that little seed crystal to start growing again – like those crystals kids grow in a jar underwater.

But the message needed to be very pure. There is a lot of crap written about Cezanne. He said very little himself, and so everyone pushes their own agenda using the great man as the barrow.

I ignored what people said about him, and went back to what he had said himself, by reading his letters, and I tried to fit that in with how he painted. It is not easy to figure out; it’s not consistent, and I’m not claiming I got it right, but then, if he’d got it right himself he would have stopped painting, and he never did that.

I am certain of one thing though – the message is to observe nature. Remove self, and observe nature. This is one of those things that’s easy to say but impossible to do. This is why he was able to keep at it his whole life, because the contradiction makes it impossible.

Removing self from painting is like saying “Imagine you’re dead.” If you’re dead then how do you know you’re dead, hey? Gotcha. This does not mean it’s a bad idea to try though. It creates a struggle, a tension, and I think this tension has something in it that makes the work. It also kept him going. It’s not like he painted one apple and said, “Nailed it, I can stop now.”

Study nature, learn to see, remove self. I can’t stress enough how hard this is to understand, but that’s a good thing. It wouldn’t be fascinating if was easy. It’s tantalising – it seems as though it’s there but it’s not. The answer shifts and turns, slips through you fingers then reappears hovering again, just out of reach, beckoning.

You can’t say what this thing – the goal, the search, the struggle – really is. If you could put it in words you wouldn’t need to paint the pictures. Cezanne could not say what it was either, but what he could do was devote his life to it, and that’s what he did.

So why does photography belong with painting as part of this conversation? For me the processes are aligned because the intent is the same, and process must be the servant of intent. I believe that photographers should learn to see deeply, to be receptive of what is there but not quite visible.

As photographers we choose our place, we choose our moment, and we make an image. The image is all we have, and we owe it to that image to be as sure as we can be about what we are doing. We’ll never really know, but we need to try. It’s partly about truly knowing our subject.

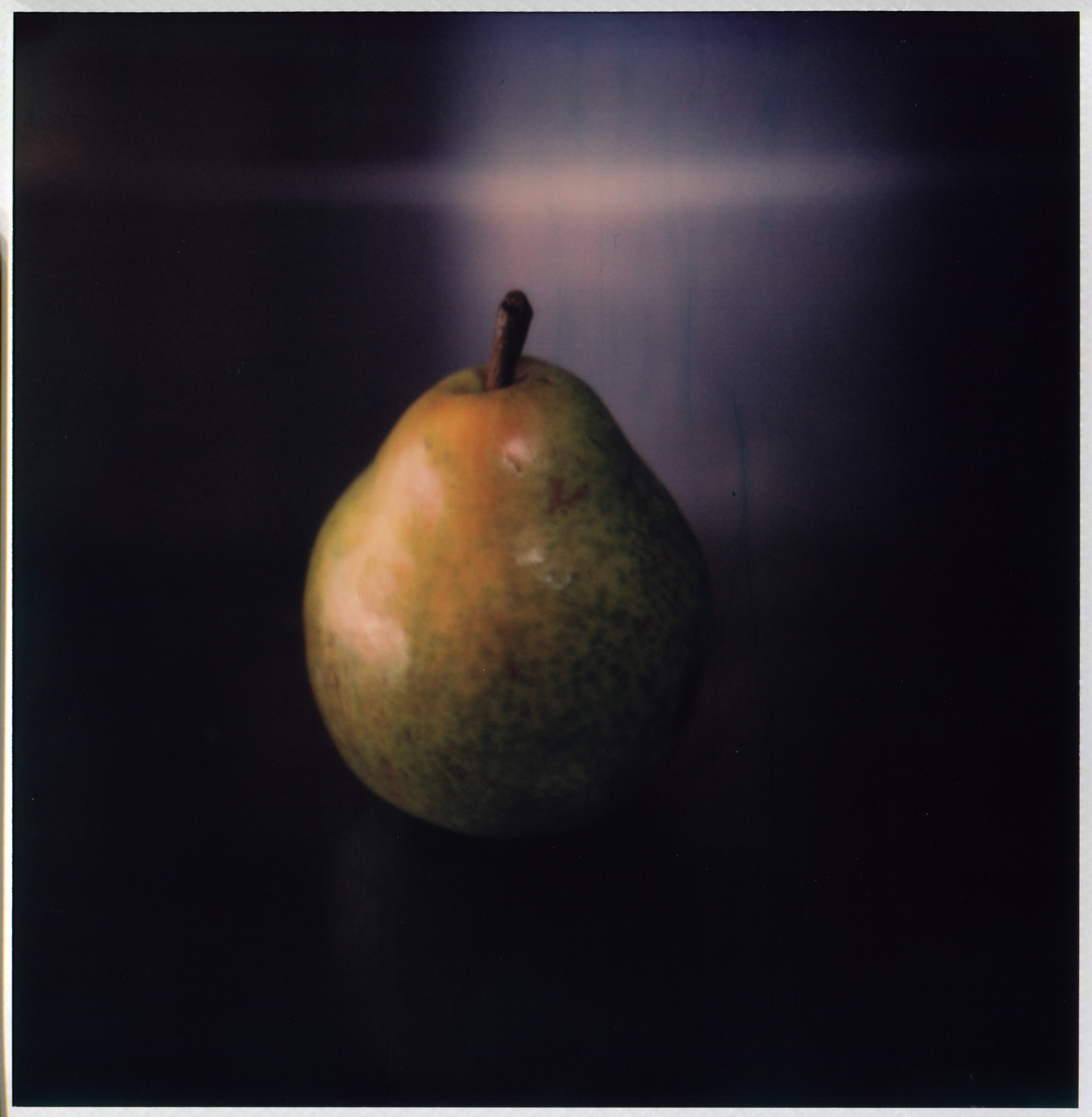

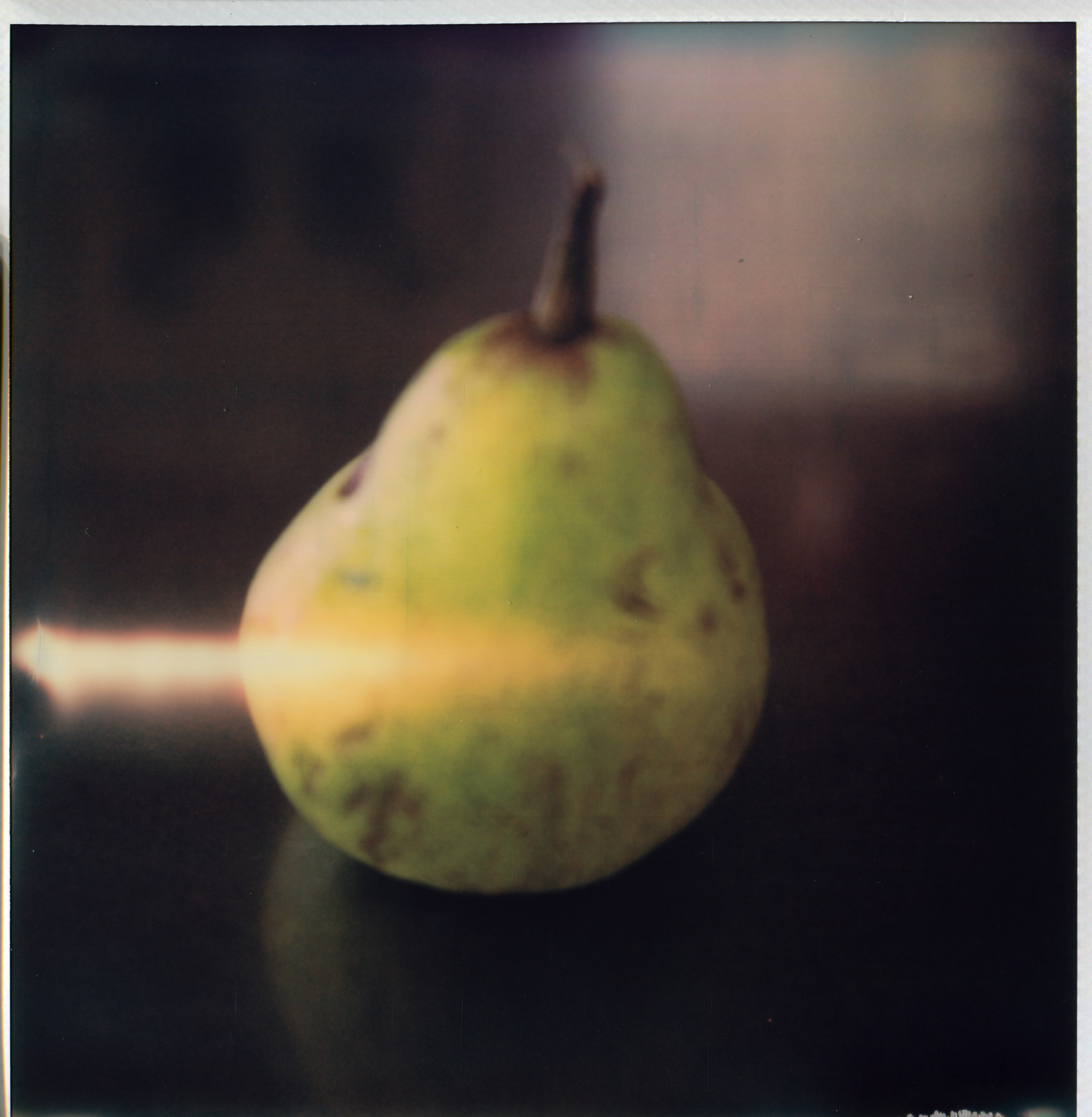

I claim a right to photograph my lemons and pears after years of drawing them; a process that is is a partner to seeing. Photography must contain respect for process, respect for subject and respect for place. It involves caring about where we are and what we are doing, and trying to look out, seeking some of the sublime that we can never really find, but that we have to keep looking for, because we know it’s there and we feel it and we want to be able to show it to others.

My purpose in exhibiting these photographs and saying, “but you see, they are the same as the paintings,” is to have at least one mindful person say, “that is absurd,” and then, some time in the future, perhaps in ten years, to have them say, “no, that is not absurd.”