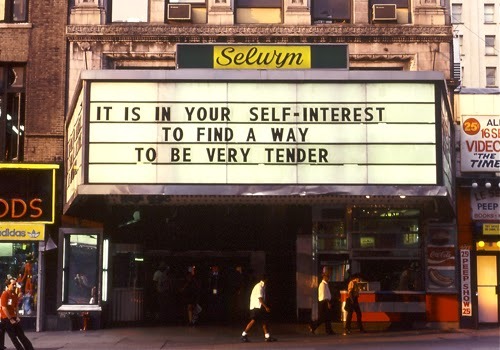

In the 1990s I had come across Jenny Holzer and her Truisms, and they resonated with me then as they still do today. My first contact with them had been through their depiction on signs outside buildings in New York – this was some years after the Truisms were pasted as lists to billboards in NYC.

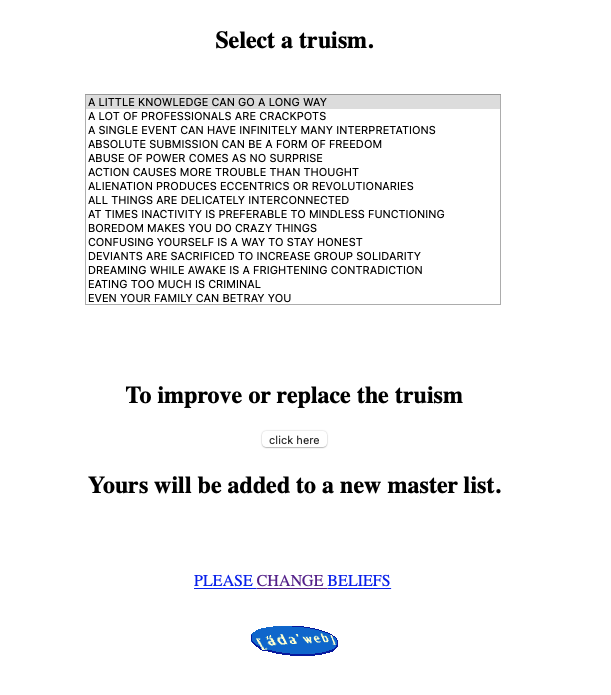

It was also the time I was introduced to the internet. “So – what use is the internet?” I asked a friend in the 1990s. “Can I find out stuff here that I can’t find out in other ways?” And so via his dialup connection I used an embryonic search engine (was it AltaVista?) to search for Jenny Holzer. It was paydirt immediately. I found a link to a site called äda ‘web where I found Holzer’s Please Change Beliefs – a web-based work that used her Truisms in a new way. Behind the list of Truisms there was a cgi script and the promise of the creation of a new list. Whether or not anything ever came of this however, I don’t know.

Äda ‘web ran from 1994 to 1998 when it was archived. It’s still around today, and some of it still works. www.adaweb.com To my eyes what was most remarkable about this early digital art was the way the cold functionality of a website had been subverted to make art.

The whole idea of websites at that time seemed to be to put information across in the simplest way possible. There was no bandwidth to be wasted on frivolities like graphics. Navigation followed simple rules.

And yet here were early websites that were were artworks, or were they artworks that were websites? I found the whole thing intriguing. Certainly they were websites, but made in a way that was unlike others.

The idea of clear, simple navigation was obfuscated to the enigmatic. Menus were counterintuitive or nonexistant and the rules were corrupted.

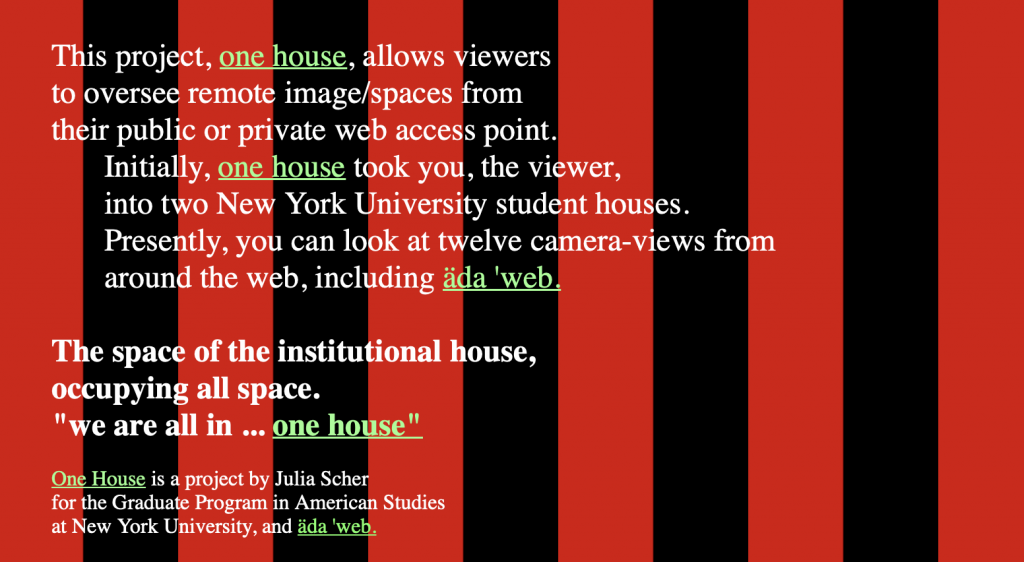

Apart from Holzer, the work that struck me most was by Julia Scher and titled Welcome to Securityland (1995). This was part of a larger project that I revisit later in the post.

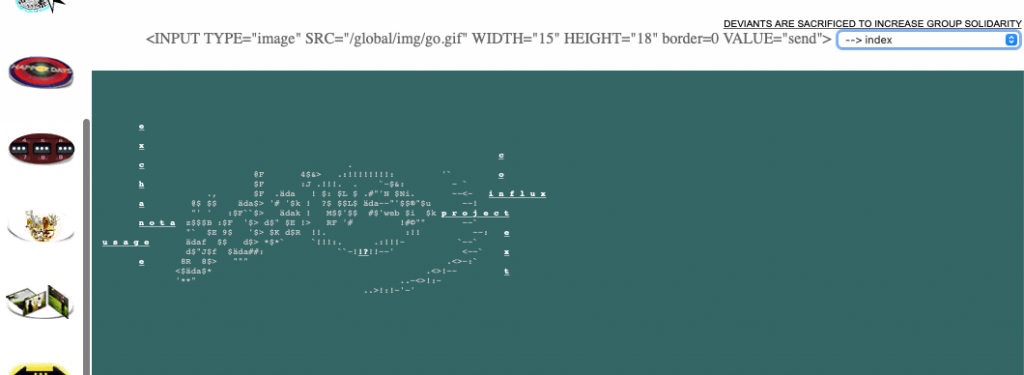

While the works were mysterious in some ways, in others they were very transparent. Much of them was static html, and by using the browser “show page source” function it was possible to see how they were made. This can’t be done nearly so easily with today’s dynamically generated html.

So – examine the sites is what I did, and I hacked my own. In fact, I became a web guy, making websites for clients (amongst doing other things) for about twenty years until I retired.

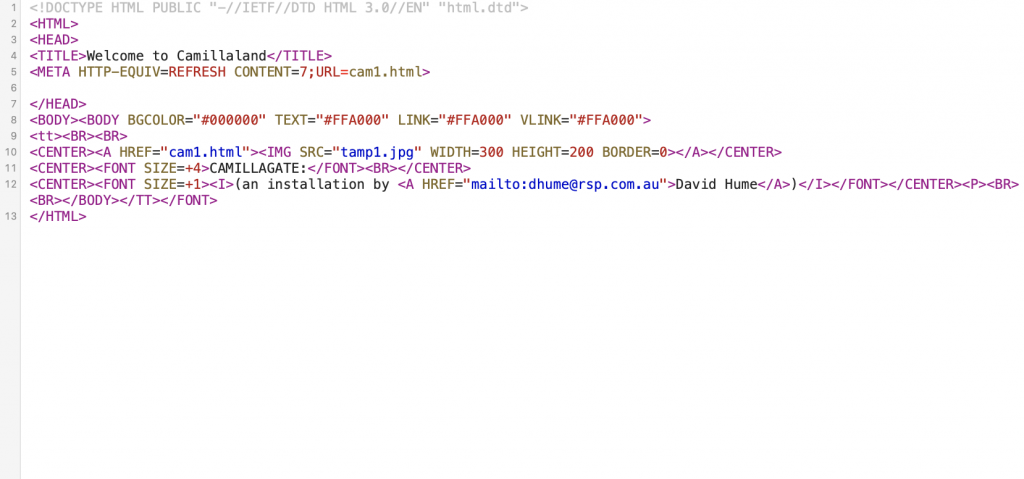

The first site I made, in 1996 was called Camillagate, starting with code I hacked from Securityland and changed so it would work for me. This was in the days when Windows would only allow three characters in a file extension, so I had to manually change the files from .htm to .html when they were uploaded. Yeah.

I found these old files in my archive so I dusted them off and put them up on my server here: https://www.davidhume.net/camillagate/

They were incomplete and I had to fix them up a bit, but I deliberately did not improve them. The site works today just as poorly as it did back then.

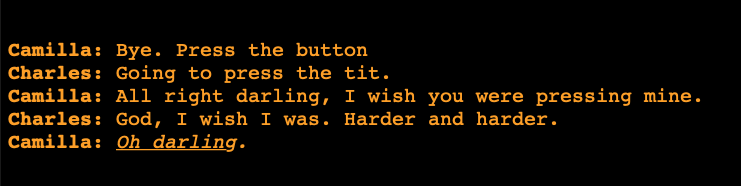

The idea behind the site was as follows. Camillagate was the name given to the infamous recorded conversation between Prince Charles and Camilla Parker-Bowles. It became public in the early 1990s and in 1994 the entire transcript was published for the first time in the Australian edition of New Idea.

I found a copy of this New Idea in a rented beach house, and had the notion that I would use it to make an artwork. I formulated the conceit that this edition was a holy text – the font of all wisdom, and all the knowledge that anyone needed to live a full life was contained within it.

Apart from the Camillagate transcript, much of the issue was given over to advice about addiction to the oxazepam group of tranquillisers, and advertisements for women’s sanitary products. I used these as the basis for a bunch of text, and used a few extra images from antique erotic postcards for good measure.

As an artwork and as a website my Camillagate is pretty bad. It has not improved with time either. But dusting it off and looking at it again after twenty five years has been instructive.

It uses deliberately confusing and obtuse navigation – as did many of the sites I found on ada web. In some pages there is no navigation at all – it relies on a meta-refresh to take the viewer to the next page after a set time. Like Securityland it is circuitous and confusing, but it eventually leads to the full transcript of the Camillagate tape. In its structure it borrows most heavily from Securityland, but I also aimed for a bit of Holzer enigma.

In revisiting this project I spent a bit of time poking around in adaweb and it was somewhat disconcerting. The pages now have all had google analytics added to them that was not there originally of course, and these days it’s harder to tell which bits of the sites don’t work because they are broken, and which bits were meant to be that way. A relic of another time for sure, that left me feeling somewhat uneasy.

For the purposes of this post I revisited ada web and poked around in some of the old sites that inspired me. I guess the message I’m carrying with me is that by comparing what we see then and now in digital art, we are still led to a large degree by what the platform allows. These early sites subverted the expectations of what a website should be and what html could do, but they were still very much bound by it, just as today’s lovely animations that pop up in my Insta feed are governed by things like the programming language Processing.

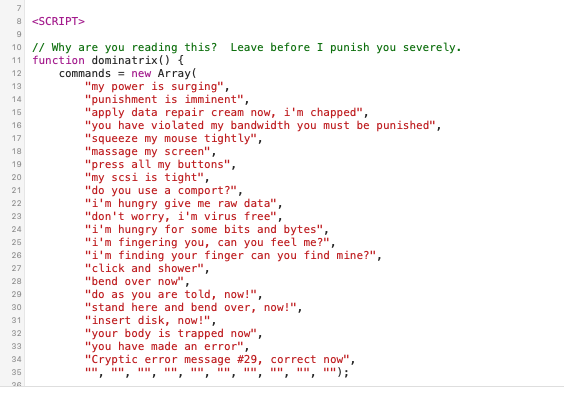

Many of the sites I visited left me feeling a bit uneasy. It was almost as if I were walking through a Cold War warehouse of mothballed military hardware. It was all out of date, but you never knew when you’d find something dangerous. The following is from a piece called “Wonderland Falling http://www.adaweb.com/project/secure/kk/

Thanks for reading.