Thomas Gloyn studied photography at Adelaide’s Centre for Creative Photography and now teaches there. I spoke to him just before the opening of his first solo exhibition while we walked around the show.

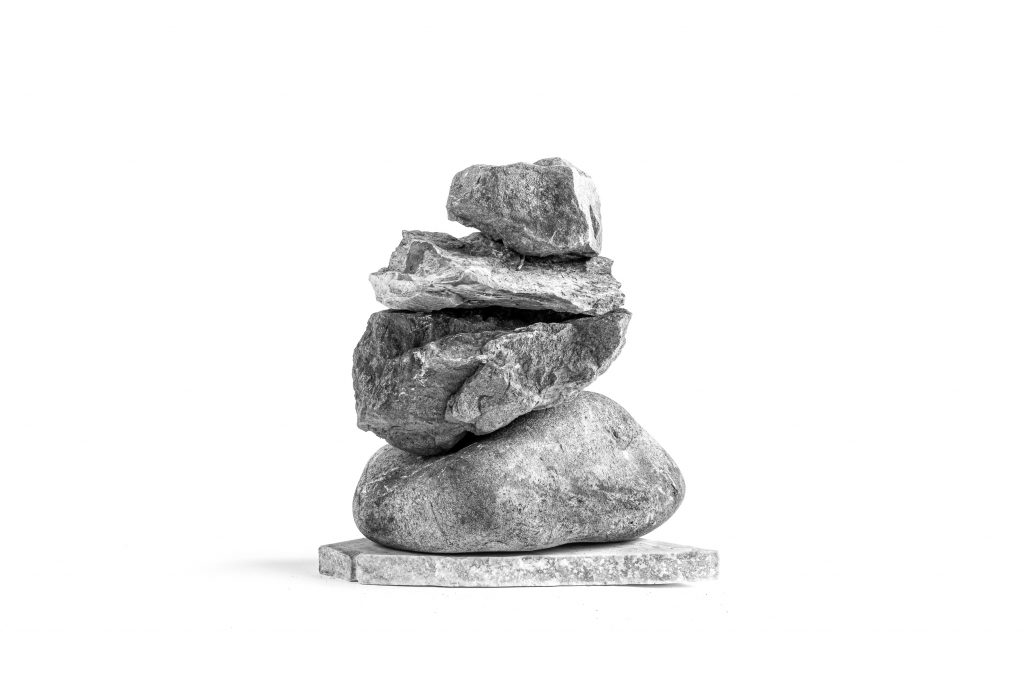

Thomas I’d like to use this piece as the catalyst for the conversation because it seems to sum up your process for me. It’s a shot of natural objects, but it’s carefully lit with studio lighting, and there’s a lot of care with the printing; so it speaks to quite a few aspects of your work. Would you care to elaborate?

“These are just some rocks that I brought in from my garden, but cairns in general are very interesting to me because they are a such a rudimentary form of human affirmation. It’s one of the simplest form of sign, of saying ‘we were here.’ So I’ve taken that simple sign from the outdoors and brought that into the studio.”

It’s probably now worth mentioning that we’re looking at a series – this is one piece from the series that forms your exhibition “A Young Man Sees (and other stories). Tell me about this idea for a whole bunch of images, each presented with text, that together forms this show.

“Well, they’re simple tableaux or vignettes, they are mostly simple subjects on a plain background – the idea is just to give people a little bit of narrative, so they can form their own ideas.”

I’m seeing your show now for the first time and it’s giving me a lot to take in. It seems the text is very important. I mean, in the past I’ve seen straight landscape photography from you and this really has another layer of complexity.

Well, the last work of mine that you saw was landscapes, and this is totally different- a different line of thinking.

I’m detecting that there’s a lot of thought about the nature of the photographic process here. As you say, each piece is a tableau, but it seems you’re saying, “Okay – in each of these pieces I’m going to show you something, like ‘here’s light through glass,’ or ‘here’s formal composition,’ or ‘here’s tonal range.’” Would you speak to that statement – because in this show we don’t have any found pieces; they’re all constructed.

Precisely. And that’s where the idea of tableau comes in. These are all composed, all made from scratch, Many were drawn up as concept images first, and that was integral to the process. I draw as well, so these started as ideas and were built from the ground up, so to speak. And yes, the technical aspects, the fact that they’re all lit with studio lighting, that’s part of the process as well. That’s a nod to the technical photography that I’ve studied, to the techniques that I now teach to others. But I don’t want to be known just as a technical photographer.

Right. But I sense an element of you sharing a bit of your joy in the process of image-making?

Oh, for sure. I mean, I love it. I love studio lighting. I see it as problem solving. You’ve got an image in mind, you have an idea of what you want to achieve with the light, of what you want to create with that. You have to figure out how you want to shape the light. Yes, I very much do enjoy that process. And doing this work – showing it like this – is a step outside my comfort zone. I mean, a landscape is a landscape but with this work there’s a chance that people won’t get it.

Well I think that’s an interesting point in it itself. I mean, you know it’s a hobby-horse of mine that you can’t beat people over the head with a manifesto, you can only invite them in, and see if they have a look, and then if they have another look, and then maybe a third look and go “Ah!” And I think that’s the thing about text; I think whenever text is introduced to work you need to be careful that you don’t say too much. Maybe you could tell us about the relationship between text and image in this work.

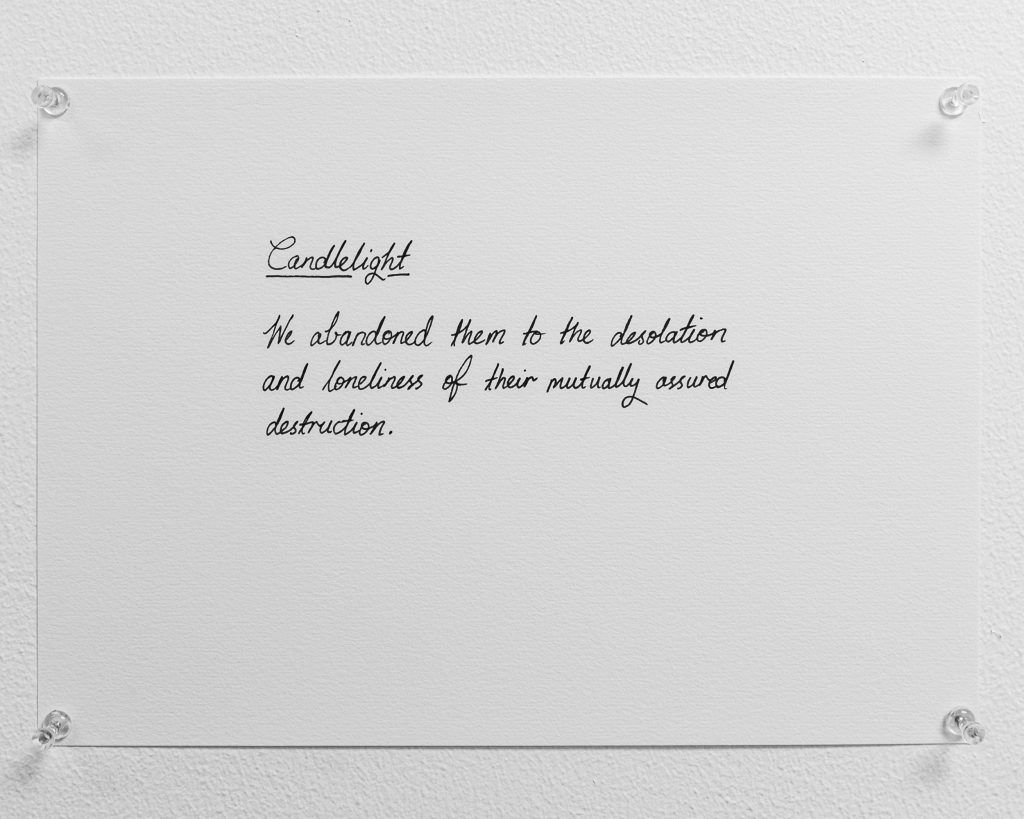

Perhaps we could say that in each of these pieces – in each of these tableaux – there’s a story, and then the text is the first sentence of that story. And then in some of the other pieces the idea is are a bit more abstract; they’re a bit more allegory.

Would you view the text as the starting of a narrative? Perhaps the starting of a conversation between you and the viewer?

I think it’s probably more of a case of the text giving you – the viewer – a bit of an insight, a bit of a clue as to how I’m feeling about the image I’ve just made.

Okay – because I see the text as opening up a discussion. A dialogue. I’d say it changes the relationship between the viewer and the work because it says to the viewer, “Look; this is more than me just showing you that I know how to make a picture.” For example there is one piece that is very simply a candle burning at both ends; nothing more. With no text, you – Thomas Gloyn – don’t own that image – it’s just a popular metaphor. All you’re telling me is that you know how to light and you know how to shoot; well so what? But once you’ve put your own piece of text in there it becomes an invitation to the viewer to go somewhere with you.

I think Invitation’s a very nice word.

With the text, all of a sudden there’s a story that starts coming alive because you’re giving the viewer a bit of extra information about why you’re doing this; where the story might lead.

Yes, the captions – the statements – are saying that this is more than what you might see at face value. It’s saying that, yes, there’s a reason I’m doing this. It goes beyond the mere creation of an image, beyond the technical. I’m inviting the viewer to explore that further. And I guess if we go back to the title – to that piece – the young man seeing – he’s seeing something that I’m inviting the audience to come along and see as well.

Great. Well thanks for that Thomas. I think the show works really well. And the artist’s book you’ve made to go with it is a killer. Thomas’s exhibition “A Young Man Sees (and other stories)” is running at the Light Gallery in Richmond through August and September of 2021. More on the Light Gallery here . Thomas’s website is https://thomasgloyn.com and his Insta is @thomas.gloyn